Stopping Underage Sex Trafficking in the Digital Age

Snapchat, Kik, dating apps — whatever the latest technology craze, Christi Decouflé is constantly downloading and learning it. But it has little to do with any personal social media habits. For Decouflé, a detective at the Phoenix Police Department, it’s part of the job.

“Wherever the younger generation is, that’s where the predators go,” she said.

Sex Trafficking in America, a new film from FRONTLINE, follows Decouflé’s unit, which focuses on sex trafficking cases and child sexual exploitation. Since she began investigating sex trafficking cases in 2005, Decouflé has seen a shift toward traffickers using the internet as a marketing tool. So she and the rest of her colleagues — many of them women — have used the anonymity of the internet to launch a different type of undercover operation, one aimed at busting traffickers.

“Our investigations are constantly changing because we have to continually develop new undercover profiles and learn a new app constantly,” she said.

According to a report from Thorn, an advocacy organization that seeks to end child sex trafficking, online advertising for sex trafficking has been on the rise for the past 15 years. Before 2004, 38 percent of online trafficking survivors had been advertised online. Since that time, according to the survey, it had jumped to 75 percent.

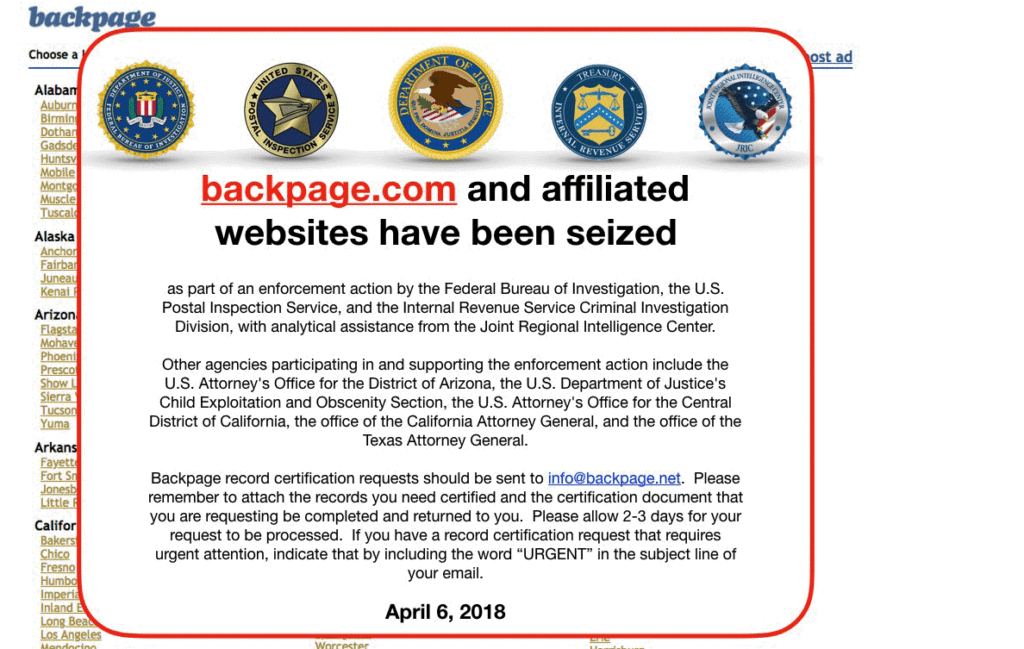

The most frequently reported advertising platform in the Thorn study was Backpage. In 2017, a Senate investigation found that the sex marketplace site had knowingly facilitated the trafficking of minors by editing ads that might have indicated that a person was underage. Backpage was seized by U.S. law enforcement agencies in 2018.

Days after Backpage’s seizure, President Donald Trump signed a pair of bills, Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act (FOSTA) and the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act (SESTA), into law. The bills — which cited Backpage, specifically — aimed to curb sex trafficking sites by creating an exception to an internet “safe harbor” rule. That rule, Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act, provided protection to website publishers if third parties posted prostitution ads.

FOSTA-SESTA changed that. With the Section 230 exception now in place, websites are held liable for prostitution ads on their site. After FOSTA-SESTA’s passage, Craigslist took down its infamous personals section and a wave of other websites followed suit — shutting down completely or removing portions of their websites used to advertise sex.

Sex workers and civil rights groups like the ACLU quickly came out against the FOSTA-SESTA for what they believe is a threat to freedom of speech. They’ve also criticized the law for not differentiating between sex trafficking and consensual sex work, which advocates say disproportionately affects vulnerable groups by making it harder for them to safely screen clients.

But advocates for sex trafficking survivors hailed FOSTA-SESTA, and the subsequent removal of sites like Backpage, as a victory.

“We’re taking away one of the weapons these traffickers have,” said Dominique Roe-Sepowitz, director of Arizona State University’s Office of Sex Trafficking Intervention Research.

For investigators, FOSTA-SESTA has presented unique challenges. The splintering of hubs like Backpage means that traffickers have turned to social media platforms and dating sites, which aren’t explicitly designed to advertise sex. Now, much of the activity is done in one-to-one communications instead of out in the open. Detectives like Decouflé have had to work to keep up.

“It’s hard because a lot of the recruiting and advertising is happening on regular dating sites and places hard to monitor,” she said.

With the shuttering of sites notorious for advertising sex, investigators are also losing evidence sources and tools for tracking down traffickers.

“We were able to gather a lot of data that has enabled investigations and prosecutions to go forward, and now we’re hearing from law enforcement that those tools are now out of their hands,” said Jean Bruggeman, executive director of Freedom Network USA, a coalition of anti-trafficking organizations.

Critics of FOSTA-SESTA say that the laws are too vague. In a letter to the House Judiciary Committee, the Department of Justice called on lawmakers to amend the language of FOSTA to focus on traffickers specifically and not cases where “there is minimal federal interest,” such as when an individual is engaging in consensual sex work.

The letter also pointed out that language used in FOSTA may have unintended consequences in prosecuting sex traffickers by “creating additional elements that prosecutors must prove at trial” when the burden of proof is already high.

Traffickers won’t disappear because of FOSTA-SESTA, Bruggeman said, but will instead move offline or to the dark web. She believes that a better way to stop minor trafficking is to invest resources in making sure that youths with troubled backgrounds have more safe spaces to turn to.

“What the law fails to do is address that that crux of the problem, which is that these kids are running away from the systems that are supposed to be protecting them,” said Bruggeman. Polaris, an anti-human trafficking advocacy group, found that being involved in the child welfare system or being a runaway or homeless youth are among the top five risk factors for a minor to be trafficked.

For law enforcement like Decouflé, the jury is still out on FOSTA-SESTA. She agreed that the guidelines were too vague — though she felt that the laws were still a step in the right direction. It would still be a while before she could say how effective the laws are.

“There’s not a lot of specifics on what to charge them with or what the expectations are,” said Decoufle. “There’s going to have to be some test cases on how you actually prove that people running the site are benefitting from this content.”

Source: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/stopping-underage-sex-trafficking-in-the-digital-age/